Hello friends,

Welcome back to my newsletter where I share short, poorly edited notes about stuff I find interesting.

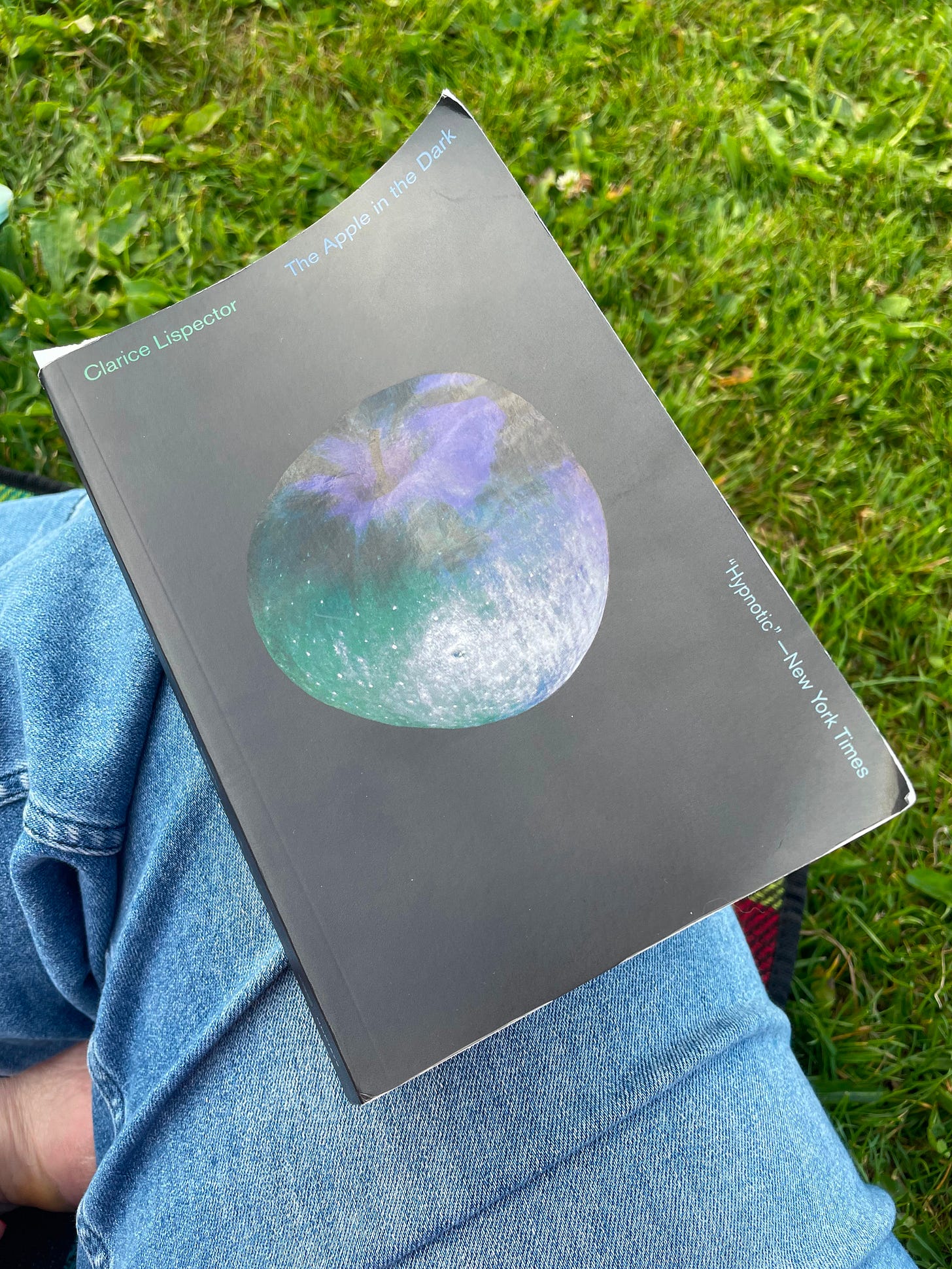

I didn’t know much about Clarice Lispector when I ran across her book The Apple in the Dark–only that her name popped up once in a while as someone that serious writers liked to read. If I’m honest, though, it was the cover that drew me in; matte black with a glossy circle in the middle that looked at first like a planet, but on further inspection was the titular apple as one might see it in near total darkness. In appearance, it struck me as the absolute opposite of a beach read, which appeals to my Gen X contrarian side (and appalls the latent Millennial in me–I’m a conflicted being).

When I finally cracked the book open, literally on a sunny beach in Cancun, I was dismayed, worried that I had been duped into buying some cheap AI generated reproduction of a book. The opening sentences were so strange as to appear to be an error:

“The story begins on a March night as dark as night gets while you sleep. The way that, peaceful, time was passing was the extremely high moon passing through the sky. Until much deeply later the moon disappeared too.”

The broken sentences, lack of certain punctuation, repetition of words, it was all so strange. And what do you do with a construction like “much deeply later”? If I ran into this in a student paper, I might suggest a resource on proper adverb use. Was this intentional?

I was so thrown by this that I jumped from my beach chair to find a wi-fi connection so I could google the edition. The internet, in its infinite wisdom, assured me that the translator, Benjamin Moser, is not only the consummate expert on Lispector, but that his many translations of her work have been praised for their faithfulness to the writer’s original syntax, maintaining oddities and quirks that had been polished away in previous English editions.

This, I realized, is the kind of writing Generative AI could never do. The weird syntax. The rules are broken in ways that aren’t lazy but hypnotic (as the book jacket promised), enticing. Long, languid paragraphs that shift in mood or even subject in the middle. An imprecision that’s so audacious it turns into precision in the end.

Accepting that this was one of those books that I’d have to learn to read while reading it, I began a journey that pushed me into the darkest recesses of the self and what it means to be human beyond the borders of language.

A straightforward summary (like the one here) in no way reflects the experience of reading The Apple in the Dark. A man, Martim, who has committed a crime that remains a mystery for most of the book escapes a hotel in the middle of the night, walks through a desert and ends up on a farm. There he is put to work by the farm’s haughty owner Vitória and he has various romantic run-ins with her frail young cousin Ermalinda. Eventually, he’s caught. One might expect a love triangle or some kind of climactic battle with police, but that’s not the kind of book you’re reading.

This is the kind of book where you’ll spend 30 pages in the mind of a dehydrated man sitting on a rock or enter into an extended ode to the beauty of cows in their barn. Martim doesn’t just work on the farm, he falls in love with it, draws it into his body. All of it, from the cow paddies to the rats that flow through his garden at night to the smelly shack he calls home. His self has been demolished by his crime and now he’s rebuilding it, reaching out for a new relationship to other people, making foolish errors along the way. The women also struggle with legibility in their own ways and the three ping off each other, never quite managing to settle or see each other in the way they could.

It’s a book that makes a lot of space for confusion and wordlessness, something that isn’t terribly in vogue at the moment. These days, we live tethered to machines that promise to make the world infinitely legible, endlessly knowable. We exist in carefully defined categories, surrendering our very being to diagnoses and fandoms and astrological signs. When one signifier proves insufficient, we’re certain there’s another one just a quick google search away. Yet we are still vulnerable to illusion, to profound miscomprehension of the hearts and minds of others, to the misleading powers of dangerous forces and to banal self-deception.

The medium of words is slippery–anyone who’s spent much time trying to say something difficult can tell you that. Recently, for example, I was having some challenges with my landlord. If I could write the perfect email, I thought, I would be able to persuade him to my side. Somehow, I didn’t calculate the fact that people rarely read long emails, and when they’re all charged up, they don’t tend to read with charity.

You can spend all the time you like trying to choose the right word but once the word is out of your hands, you really have no control over how it enters the mind of the reader or the listener. I want to quote Roland Barthes here, but I fear I’ve already maxed out on my pretension levels for a single newsletter. I’ll just stick with Lispector.

It was comforting to spend some time with a book that revels in the confusion at the heart of the self. Even Martim’s own efforts to articulate the nature of his revelations fall flat when he tries to put them into writing.

“And deflated, wearing glasses, everything that had seemed to him ready to be said had evaporated, now that he wanted to say it. Whatever had filled his days with reality was reduced to nothing in the face of the ultimatum to say.”

Eventually, staring at the blank page, he gives up on trying to convert his newfound wisdom to words. He, in fact, admits that he has no wisdom at all and accepts himself as a failure. Instead, he writes the following list:

“Things I’ll try to find out:

Number 1: That

Number 2: how to connect ‘that’ which I find with the social situation.”

What is the social situation? He can’t begin to explain. Even this, he admits, is a failure of language and a failure in his own willingness to engage with humanity’s best but flawed means of communication. I get it, Martim. I’ve had days like that.

Yet, tucked within this section is the best bit of writing advice I’ve encountered in a while:

“He didn’t know that in order to write you had to start by abstaining from power and turning up for the task just because.”

This is a hard lessons I’ve had to learn about writing. Sometimes you have to start before you even know what you want to say, and you have to keep going until something begins to click. But you have to start. You have to put that awkward pencil to page. That’s how I wrote this newsletter.

Will you understand what I’m trying to tell you? Or is it enough simply that I put the words on the page?